- Building Courageous Leaders for a Better World

January 2023

January 2023

The summer after my sophomore year of college, I failed. I’ve failed a lot of times, in many different kinds of ways, but for whatever reason, this example felt like a big one.

I talk about my biggest success of that summer more often: the chance to join a climbing team join Denali. The only team member who made it to the top— and only on our second summit attempt.

But I haven’t talked much about my failure that summer.

When I came off the mountain, I came down with walking pneumonia. But I had an Army camp to attend— Air Assault. I had made it through Airborne School the previous summer. I was convinced I could do it. I was strong. My orders required me to report on a particular day in Oklahoma, and not only did I not know that there was a choice, I was determined. I arrived at Ft. Sil with my temperature reading 102 degrees, and I showed up at zero day— the obstacle course.

And I failed.

Yes, I had arrived with a fever, and that was surely a factor— even a significant one. But the fact remains that I failed, both in poor decision making to attend and in the actual execution of the course itself. I wasn’t able to return, and I never earned the badge. I boarded the plane home with a deep sense of shame, and every time I saw a uniform with the Air Assault badge (a frequent occurrence) felt a stab of inadequacy.

Like most of you reading this newsletter, I’m not accustomed to failure. But failure is a part of the path to success for every single one of us, and the greater the effort, the greater the failures on the way. Failure is a part of the journey of taking risks, and trying new things.

In the agile culture— a stark contrast to industrial era leadership models— a fail fast culture is associated with innovation and creativity. But inside or outside of the agile culture, failing doesn’t feel good.

I’ve talked about and written about failure, oftentimes failure that can be attributed to system problems. Failing in the midst of a system you cannot control, in part because of that system, is discouraging sometimes to the point of being— or feeling— unable to continue.

But grit is hardest— facing the wind is hardest, in the face of our own failings— at least that’s what I’ve found. And it’s hardest when there is a failure of relationship— that can be even harder, even if you did everything you could do.

Bishop Gretchen Evans talks about this latter example in our interview (start at 49:48 for her answer). She shares her wisdom: “If I try something and it doesn’t work, that’s a learning opportunity. But if I’m afraid of the conversation…or I don’t take a risk that I should take, that’s where I fail. We need to get over the idea that failure means I didn’t succeed…we fail …when we break relationship.”

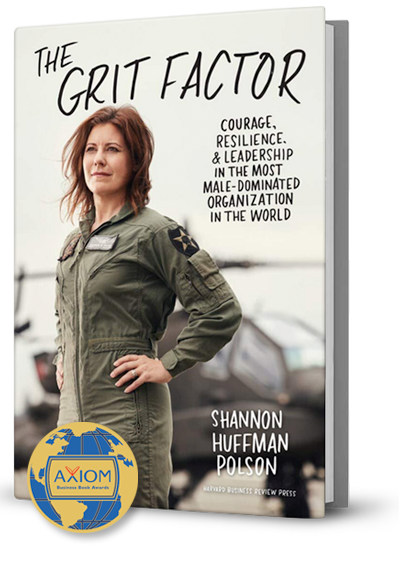

A perspective on moving forward from mistakes comes from my conversation with Erin McShane, one of the first women to earn not only the US. Army Ranger badge but also the Sapper badge. I include elements of Erin’s experience in The Grit Factor, but perhaps the most relevant aspect to the conversation today was a critical learning for McShane:

“I learned that my failure was in what I did, and not in who I was,” McShane says of wisdom offered by a mentor. “Failure was a result of the methods chosen, and not of the person. it was such an important thing to take away.” (p. 126)

Are you subscribed to Facing the Wind on your favorite podcast app? Make sure to subscribe HERE— epic episodes releasing to finish season 2!

Last spring, I interviewed retired CSM Gretchen Evans of TEAM Unbroken, and despite her astonishing career, she talked about failure in a way that truly resonated— she deals with failure, she says, the same way as she deals with success. She gives herself 24 hours to react to it, and then she moves on. (Listen in on your favorite podcast app to the interview here, or watch the UNCUT interview here).

To move on doesn’t mean to not revisit the opportunities for growth and change— but it means to deliberately give yourself permission — and require yourself— to move forward emotionally. For 24 hours, let yourself experience the disappointment, the heartache. And then move beyond shame or discouragement toward taking a step toward progress and productive solutions.

And then move.

Then move.

MOVE.

Creative inspiration:

I’m thrilled to have my poem “Hover” included in the most recent issue of War, Literature and the Arts— you can find it here, along with other excellent writing.

My essay “Holding Breath,” a lyric essay about vocal performance and more, is included in Issue 8 of the Peauxdunque Review, just out in print and available here!

Take a listen to Why We Serve, composed by Washington composer BC Campbell for the Smithsonian honoring Native Americans who have served in our military— and buy a digital copy for yourself and those you know.