December 2022

December 2022

When I was a young second lieutenant, I worked for a year in an operations shop in an Apache helicopter battalion at Fort Bragg, North Carolina before leading a flight platoon for a year (picture below with one of my pilots, Frank, on the flight line at Simmons Army Airfield). In the mid-90s, we weren’t doing much flying due to budget cuts; at one point, our money to fly ran out half-way through the year, and I remember “flying” a battalion mission on a large chalk map on the hangar floor, pilots walking the route and responding to unknowns by opening envelopes.

Then the 18th Airborne Corps was called up for Bosnia, and our regiment was told they would send one battalion. It wasn’t ours. I remember being so deeply disappointed; every pilot, every soldier, wants the chance to make their training count, to do something that matters.

And then I heard that a flight platoon had opened up in our sister battalion, the one scheduled to deploy. I talked to my company commander, who sent me to the battalion commander.

I waited outside of his office for what seemed like an eternity before he called me in. I told him I wanted to take the platoon in our sister battalion. I wanted to deploy. He didn’t smile a lot, but I remember, him saying “Hu-ah!” — which is what you say to support something in the Army and at unspecified other times. I felt huge relief. But that wasn’t the end of the conversation.

“Lieutenant Huffman,” then LTC Macdonald (retired as MG Macdonald) said, “what feedback do you have for me?”

I was completely taken aback. I didn’t think my feedback could have any bearing on anything— I wasn’t even sure what my feedback would be. But I remembered the guys in my platoon, the things they were dealing with, the exhaustion from the high operational tempo, the high numbers of divorces.

“People are tired,” I told him, at first reluctantly, but then excited for the opportunity to speak out for the people working for me for whom I cared so much.

He listened intently, carefully, and then thanked me.

He is the only leader I ever worked for in the Army who asked me that question. “Do you have any feedback for me?” Later, at Microsoft, one boss would ask me the same before he left the organization, and then asked where I wanted to be in five years, and how he could help support me.

Other versions of this question might be:

“What can I do to better support you?”

“How can I do better?”

It takes a lot of courage to ask this question, in this way. It’s opening yourself as a leader to feedback that might be difficult- but it’s also saying: I trust you. I respect you. I know that my job is to support your work. I know that I might be blind to some important things, and I want to do better.

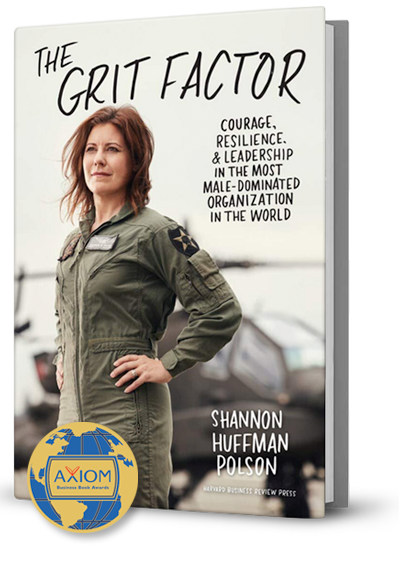

Ordering books for gifts? Here are a few suggestions!

In a time of both painful layoffs and resignations, leaders that have been asking this question are undoubtedly far head of their peers in retention and engagement— in what Microsoft is not calling “thriving." (I love that change in word and focus, by the way— that is what we all want— for ourselves and those around us to thrive.). it is no coincidence that the same battalion commander that asked me that question went out of his way to provide professional development opportunities for the lieutenants, far more than any other leader I would work for would do.

What did he know? He knew that his job was to care for and develop leaders. He prioritized that in his actions, his words and his work.

The recent McKinsey study shows two things: people leave bad leaders, and people leave because they aren’t given the opportunity to learn and grow. These are more important than any other aspect of work.

There is much shifting in the world of today, tectonic and sometimes cataclysmic movements— but at the end, it all comes down to taking care of your people, which you will know how to do if you talk with them, ask them questions, listen and reflect— and giving them the chance to learn and grow.

(Can The Grit Institute help you meet this mission as you plan for 2023? Reply to this email and let me know if you’d like to talk about your needs.)

All my best,

Shannon

PS: Looking for a new journal for the new year? I recommend the Monk Manual, a science backed journal beautifully produced to help you in planing, execution and importantly, reflection. I use Monk Manual myself, and it’s both a beautiful product and a helpful tool for daily, weekly and monthly planning. Take a look. If you love it, too, click here for a special discount!

Below: A screenshot from my incredibly important interview with Amy Conway-Hatcher about why senior women are leaving the workforce dropping imminently (you’re already subscribed, right?)— and my technique for making every day a great one.