Aristotle believes that courage was second to justice in the list of virtues. Maya Angelou disagreed: she believed courage was required in order to exercise any of the other virtues. But what exactly is courage, and what does that mean? And how does one find it or, more importantly, cultivate it?

I listened recently to the discussion on The Daily podcast about the interview with Bing, Microsoft’s search engine. The conversation left me chilled. Along with the reference to the Google engineer believing that the AI they are working on at Google, the clearly stated evil intentions, as well as the manipulative language used by the AI itself, is terrifying. It is not only this of course, but policy making and climate and education— all of these areas and many more demand courageous leadership right now, and people willing to accept the necessary cost of speaking out against systems that seem to working against us.

Let’s start by asking the question Deidre Paknad, CEO of WorkBoard, suggested in our conversation on the podcast last summer: WHAT DOES GREAT LOOK LIKE? In any endeavor? Technology development, leadership development, parenting, climate, and more?

I’m working on the next book, and interrogating courage. This post is a bit more into the research, but I’m finding it both hopeful, as well as a helpful prompt to consider the practical and real applications of courage, too— I hope you will as well, because in a world that is changing as rapidly as ours, courage is something every one of us needs, and leaders, in particular, need.

a photo from my first duty station at Ft. Bragg, NC with my back seater, Frank

For Aristotle and Angelou, courage was by necessity connected to virtue.

This is the approach I’m inclined to take as well, which is to say that action that is not virtuous can inherently not be courageous. This by itself poses a problem, given different opinions on what is virtuous. Susan Sontag, in the aftermath of 9-11, suggested courage was morally agnostic— but that is not the focus of the questioning. Suffice it to say that courage is a complex and multifaceted concept that has not yet been codified, despite the many efforts to do so.

Academics disagree on the different types of courage. It’s common to suggest six types: physical, social, moral, emotional, intellectual and spiritual, but there is more support for three types: physical, social and moral.

Courage is the willingness to face the wind:

literally, in the case of taking off in the Apache or any other aircraft. Metaphorically in every other area of our lives. Physical courage gets headlines: the firefighter running into the burning building, the climber scaling the vertical cliff, the fighter pilot. For many who live in the first world, the comforts of life and the tendency toward celebrity hold up these examples of physical courage almost exclusively for admiration.

In a world where so much is in limbo, and truth itself seems up for grabs, it’s social and moral courage that we need right now.

But what exactly ARE these kinds of courage, and how does one cultivate them?

You know it when you see it: Socrates choosing hemlock instead of exile, a choice offered to him for inciting the youth of Athens with his ideas. Gandhi fasting until the British government relinquished hold in India. St. Francis throwing away all earthly wealth to accept poverty and a life devoted to the spirit and the earth? Mother Teresa choosing to care for the poorest of the poor in Calcutta. Desmond Tutu taking a stand against apartheid. Liz Cheney’s handling of the January 6th hearing, at the expense of her career.

Hemingway famously described courage as “grace under pressure.”

But researchers are not of one mind. A more nuanced definition of courage is “‘the disposition to voluntarily act, perhaps fearfully, in a dangerous circumstance, where the relevant risks are reasonably appraised, in an effort to obtain or preserve some perceived good for oneself or others recognizing that the desired perceived good may not be realized’’ (Shelp, 1984, p. 354).”

This second definition is nearer to this observer’s beliefs, anchored as it is in the common good, and not mere bravado.

The difficulty in defining courage extends not only to understanding types of courage, but also the elements which make it up. Countless academic studies have revealed different aspects of virtue, none so clear as to become the definitive view. One study including a larger group of experts in the field of psychology suggest four components of courage:

(a) endurance for positive outcomes—including behaviors such as ‘‘acts despite bullying as a minority’’; (b) dealing with groups—including behaviors such as ‘‘help grieving family’’ and ‘‘rejection by others for goals’’; (c) acting alone—including behaviors such as ‘‘accept job despite criticism’’ and ‘‘avoid confronting my own pain’’; and (d) physical pain/breaking social norms—including behaviors such as ‘‘intervene in domestic dispute’’ and ‘‘endure pain for political secrets.’’

Positive psychologists Seligman and Peterson suggested four other related aspects of courage: bravery, perseverance, integrity and vitality.

Given that the foundational text on courage, considered by many to be Plato’s dialogue Laches, does not itself come to a conclusion, the challenges of definition are long lived. Most recently, Seligman, Peterson, Snyder and Lopez suggested the following definition: ‘‘the exercise of will to accomplish goals in the face of opposition, either external or internal.’’

One thing Laches DOES do is to determine that bravery in battle, for example, is insufficient as a definition, implying that there are other kinds of courage that are important as well. These other kinds of courage, I’d suggest, are by far the most difficult, as they fly in the face oftentimes of social acceptance.

Social courage is defined as taking deliberate action or speaking up in ways that create risk for the person’s social image. The worker takes this action for the sake of others or of helping the organization. An example of this type of courage is speaking up when a co-worker is rude to somebody, even at personal cost.

A definition for moral courage is the courage to take action for moral reasons despite the risk of adverse consequences.

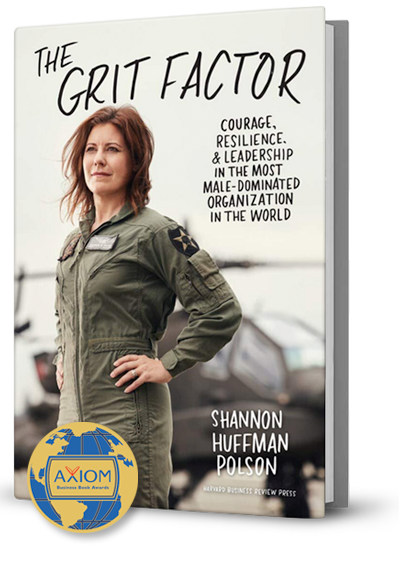

Regardless of the specificity of definition, courage is for some a moral good, and for others a good. That makes it worth pursuing. How can it be cultivated? This will be the subject of later thoughts, but let’s start with one place so that the reader isn’t let without action to take (for those who have read The Grit Factor already, or taken one of The Grit Institute courses, you’ll recognize these methods):

At the beginning of the 21st century, Gould studied the development of courage and suggested that it is cultivated by three steps:

1. growing self confidence

2. recognizing a higher purpose and

3. overcoming fear.

Let’s look at each of these briefly with an associated consideration:

Growing self confidence

In 1983, Cox, Hallam, O’Conner and Rachman measured decorated (identified as courageous) bomb operators’ physiological responses to fear and stress compared to non- decorated (noncourageous) operators’ responses. They found distinctive physiological responses under stress for decorated and nondecorated bomb operators, indicating that past courageous behavior in a particular situation will reduce one’s physiological responses to fear and stress in similar situations. These results were replicated in follow on studies.

Experience builds confidence— fortunately, experience in other areas can buttress your confidence, too.

Recognizing a higher purpose

This aspect of purpose is one with which you’re familiar from Chapter 2 of The Grit Factor. Connecting to this purpose gives us greater strength to confront challenges, and to do the right thing for a greater good despite resistance. McKinsey’s studies on purpose during the epidemic connected it to increased engagement, longevity and performance at a job, supporting the thesis. Finally, the work of Aaron Hurst in his endeavor Purpose Mindset shows that a mindset connected to making a difference vastly increases life satisfaction (and we can infer performance) as compared to the more common transactional mindset.

Overcoming fear.

Name the fear. Write it down. Name the worst thing that could possibly happen.

Name the next steps to take to reframe that fear.

Take it one small step at a time. Break up the larger objective, about which you are feeling fear, into smaller steps.

Work through discomfort by taking small steps in other and unrelated areas of your life. Remind yourself how you got through those times of discomfort or fear, and apply them to the task at hand.

I’d love to know what YOU think. What is courage to you?

How do you think about the different types of courage? And what are examples from the business world (or other worlds) that resonate for you, or that you might hold up as your North Star? I’d love to know in the comments!

Facing the wind with you,

Shannon

Creative Inspiration:

A Litany for Survival

BY AUDRE LORDE

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

for by this weapon

this illusion of some safety to be found

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

For all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive.

And when the sun rises we are afraid

it might not remain

when the sun sets we are afraid

it might not rise in the morning

when our stomachs are full we are afraid

of indigestion

when our stomachs are empty we are afraid

we may never eat again

when we are loved we are afraid

love will vanish

when we are alone we are afraid

love will never return

and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.